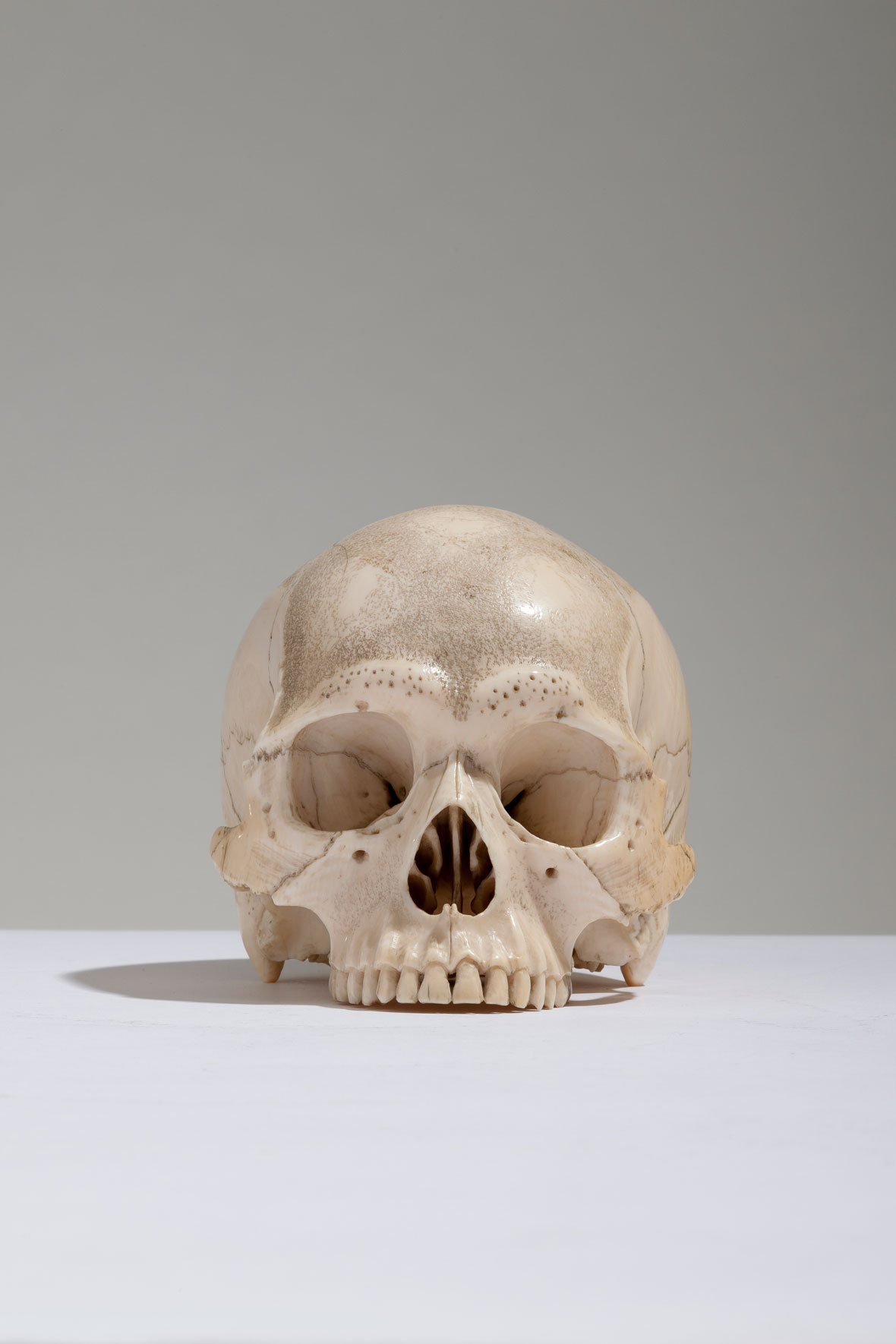

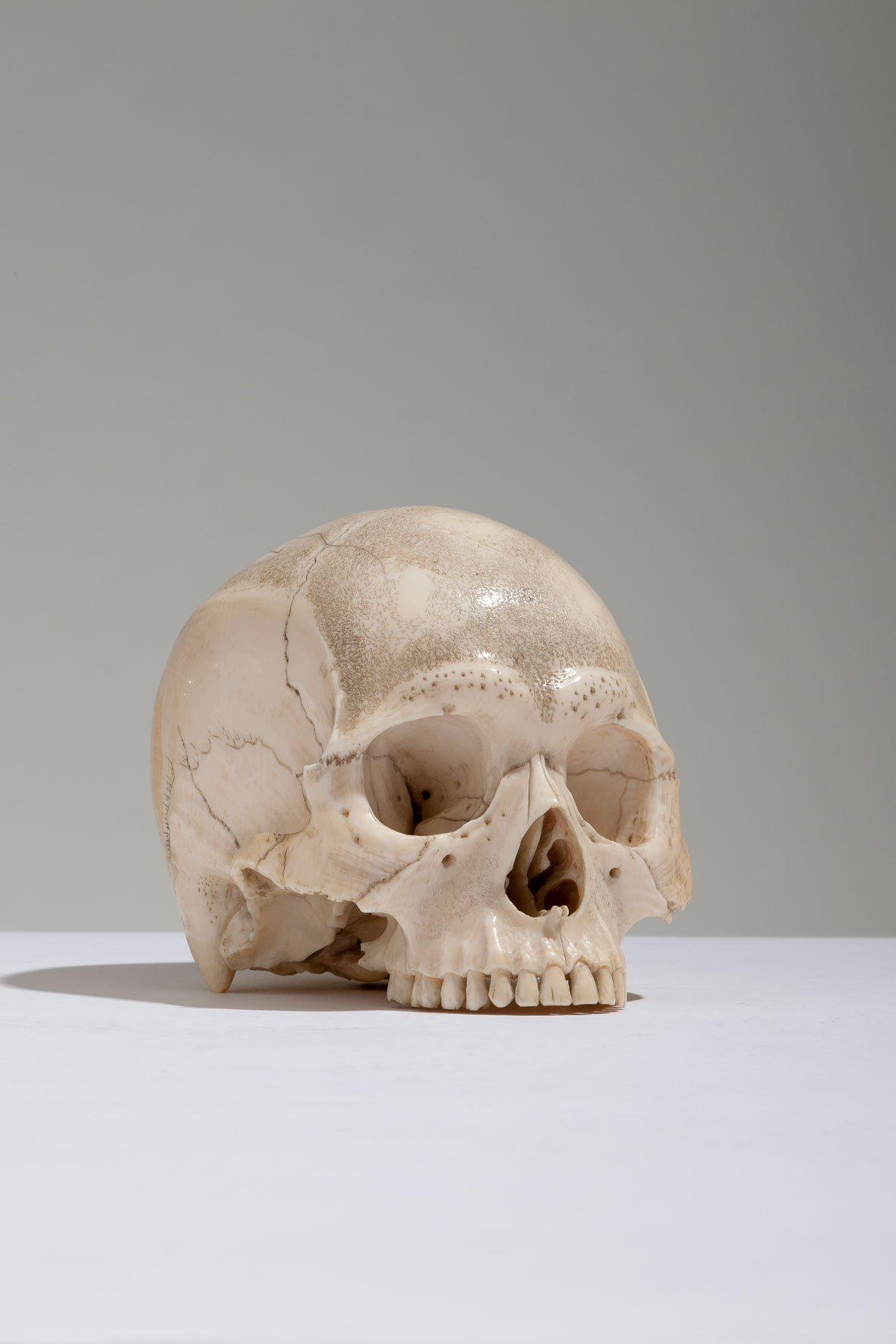

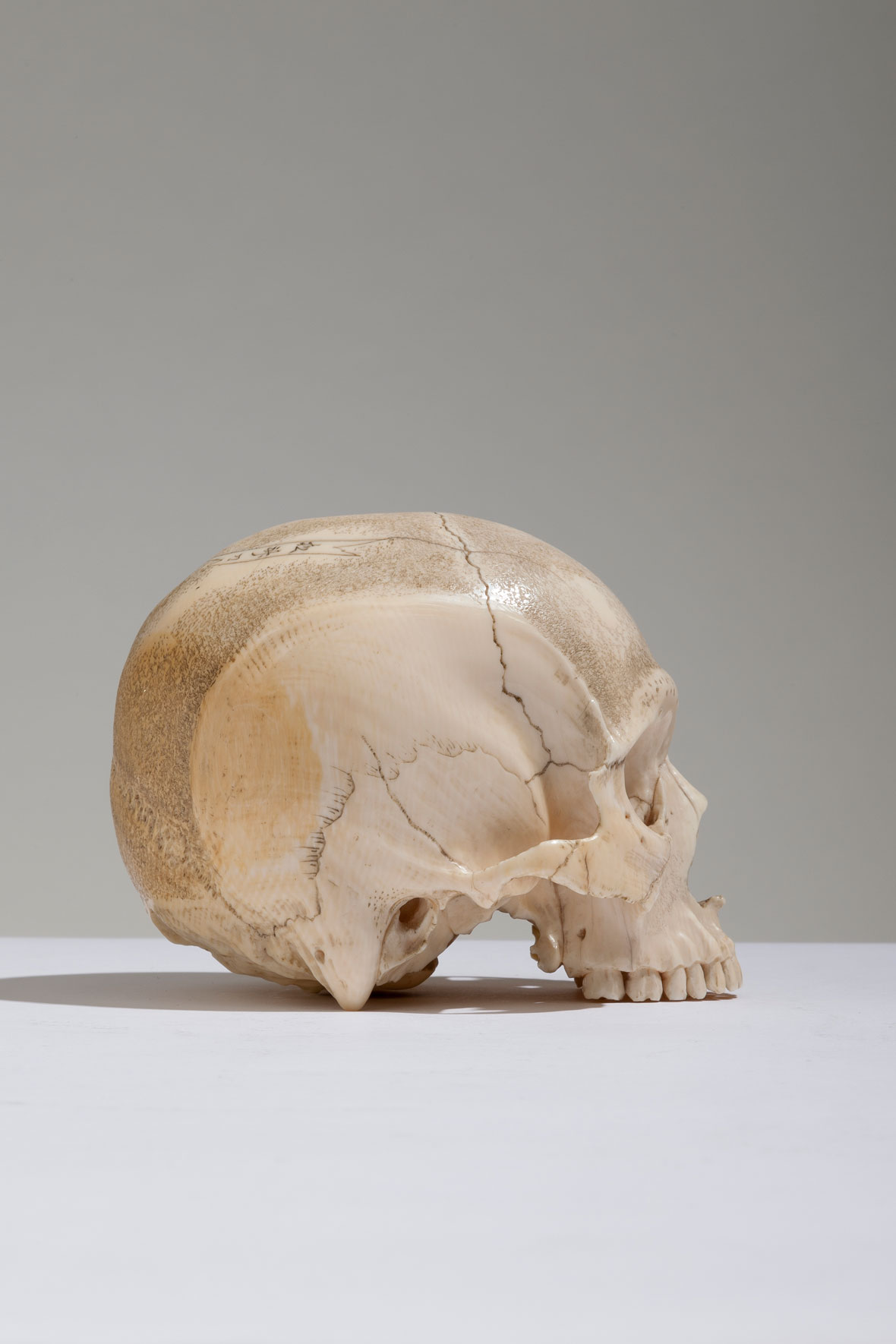

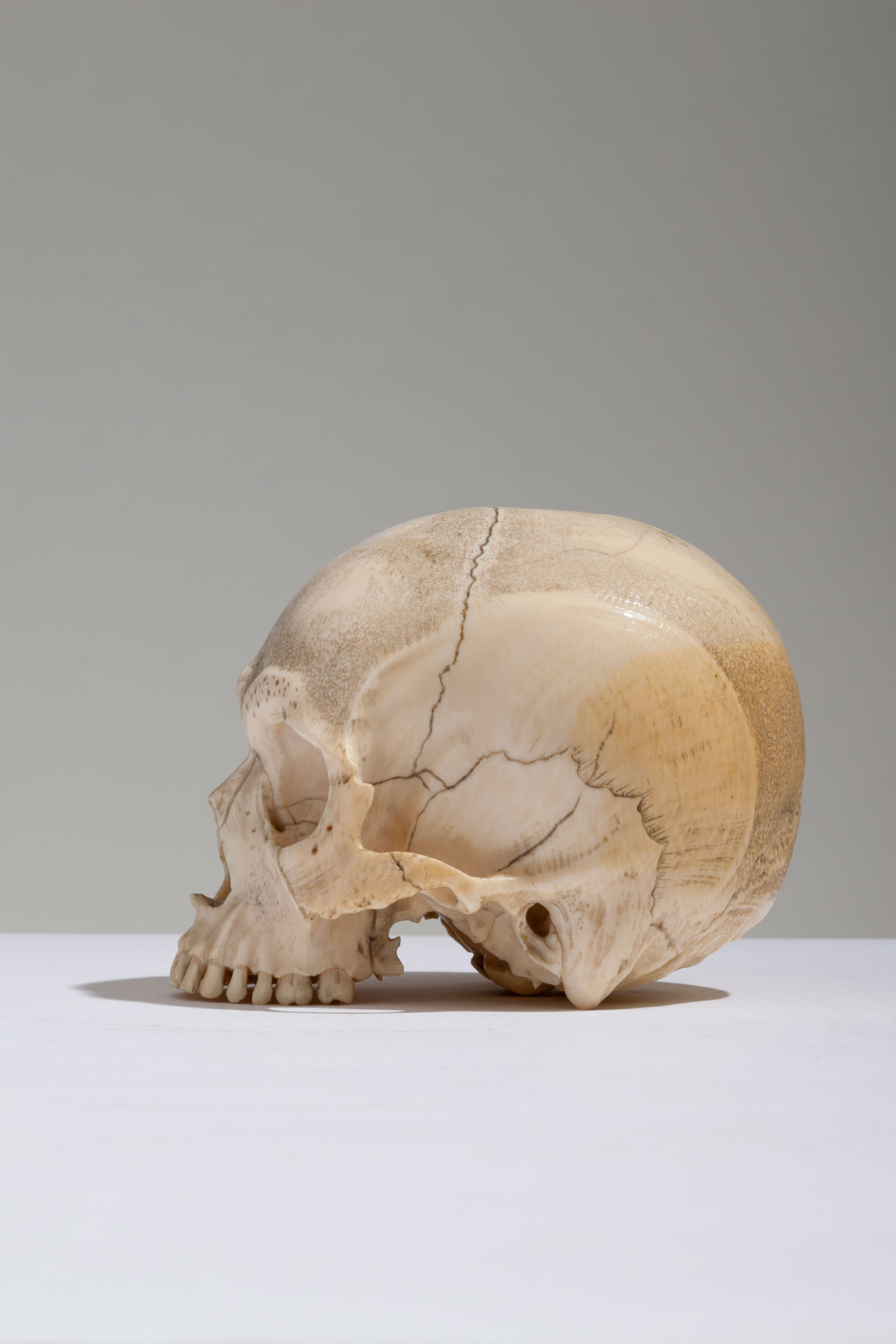

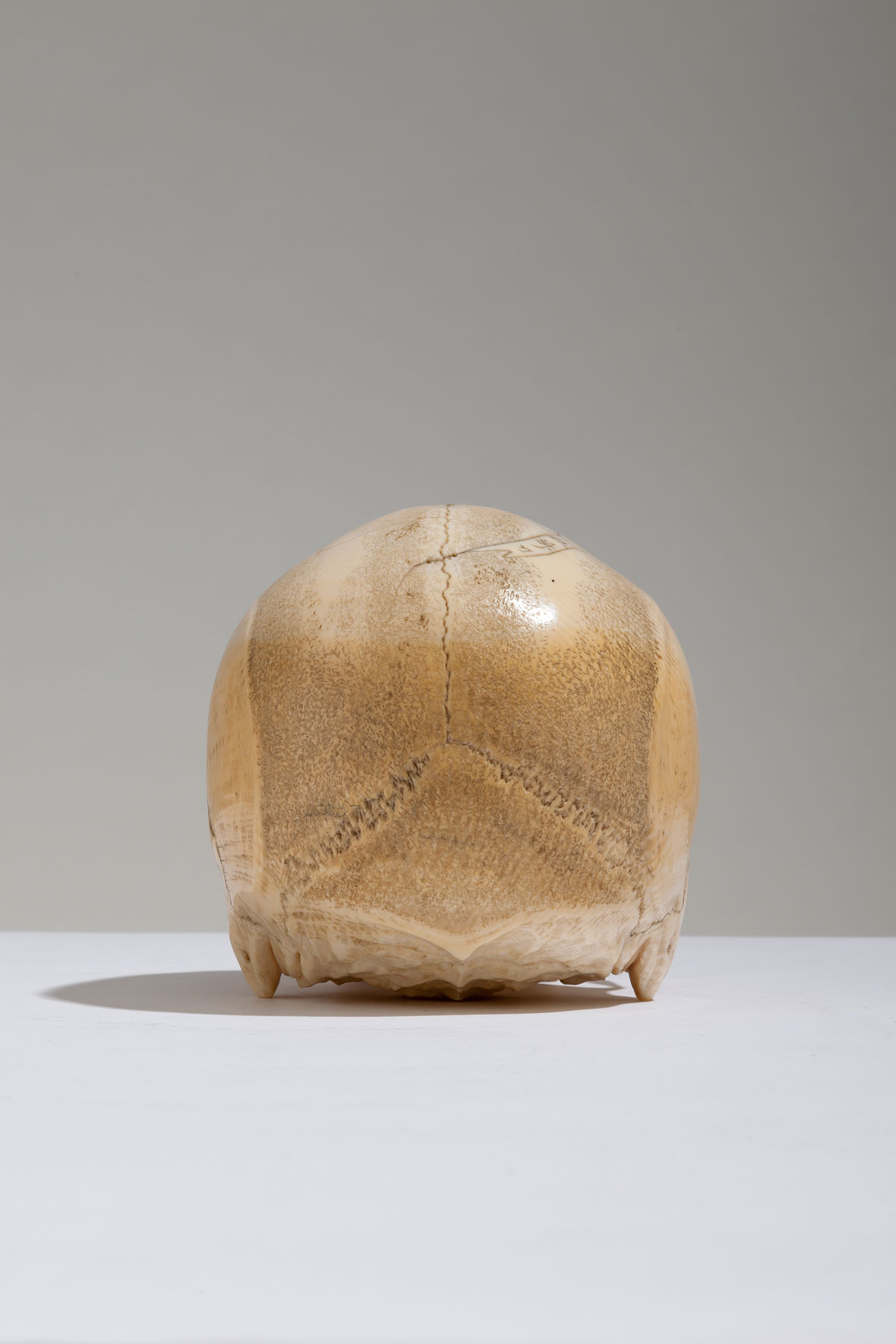

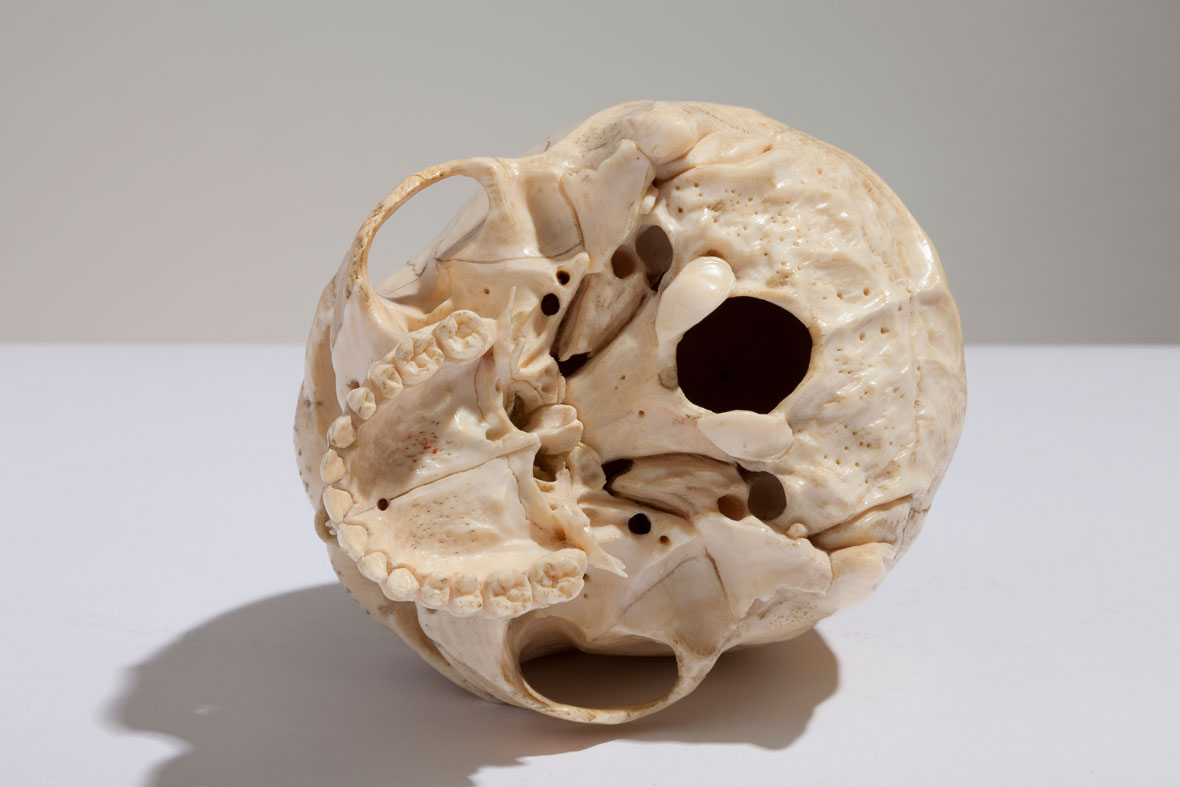

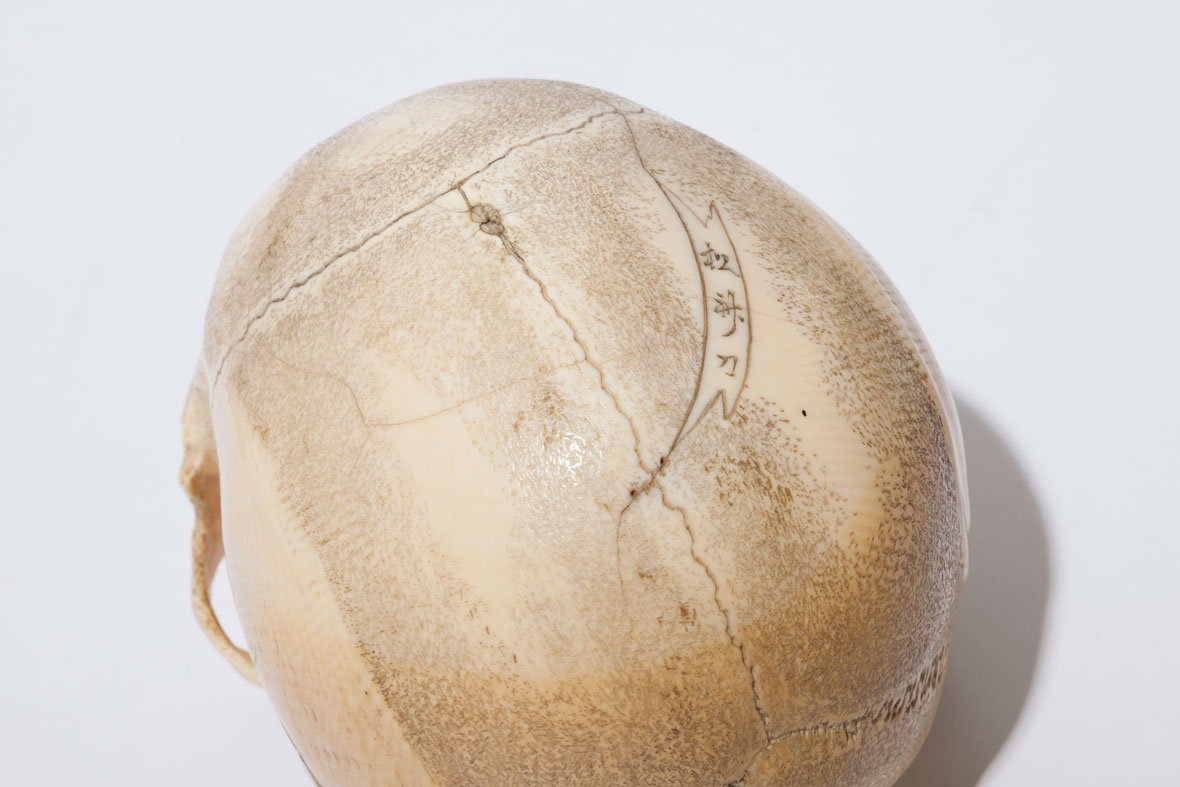

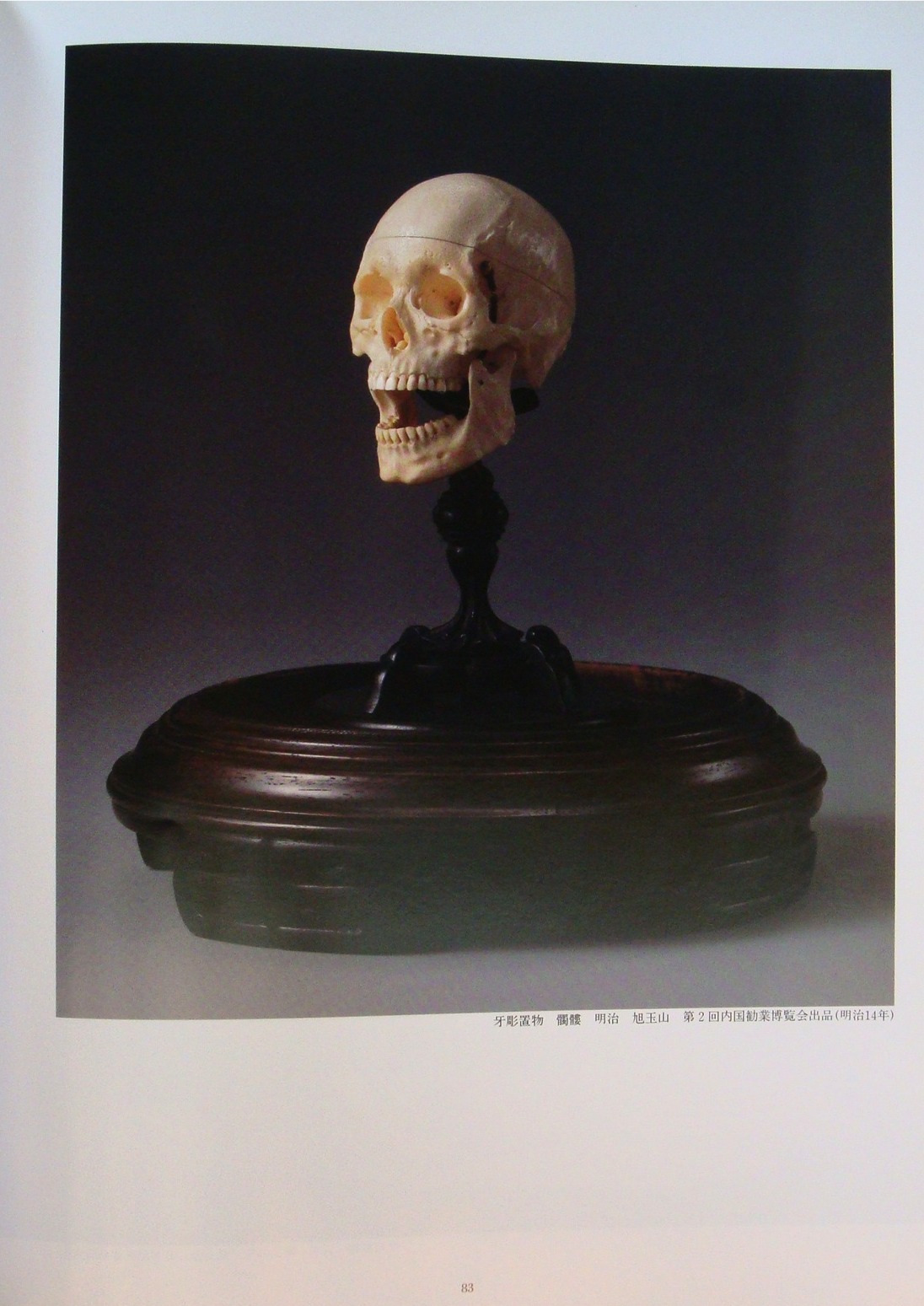

Incised Shosai

4 in (10.2 cm) high, 4 in (10.2 cm) wide, 5 in (12.7 cm) deep

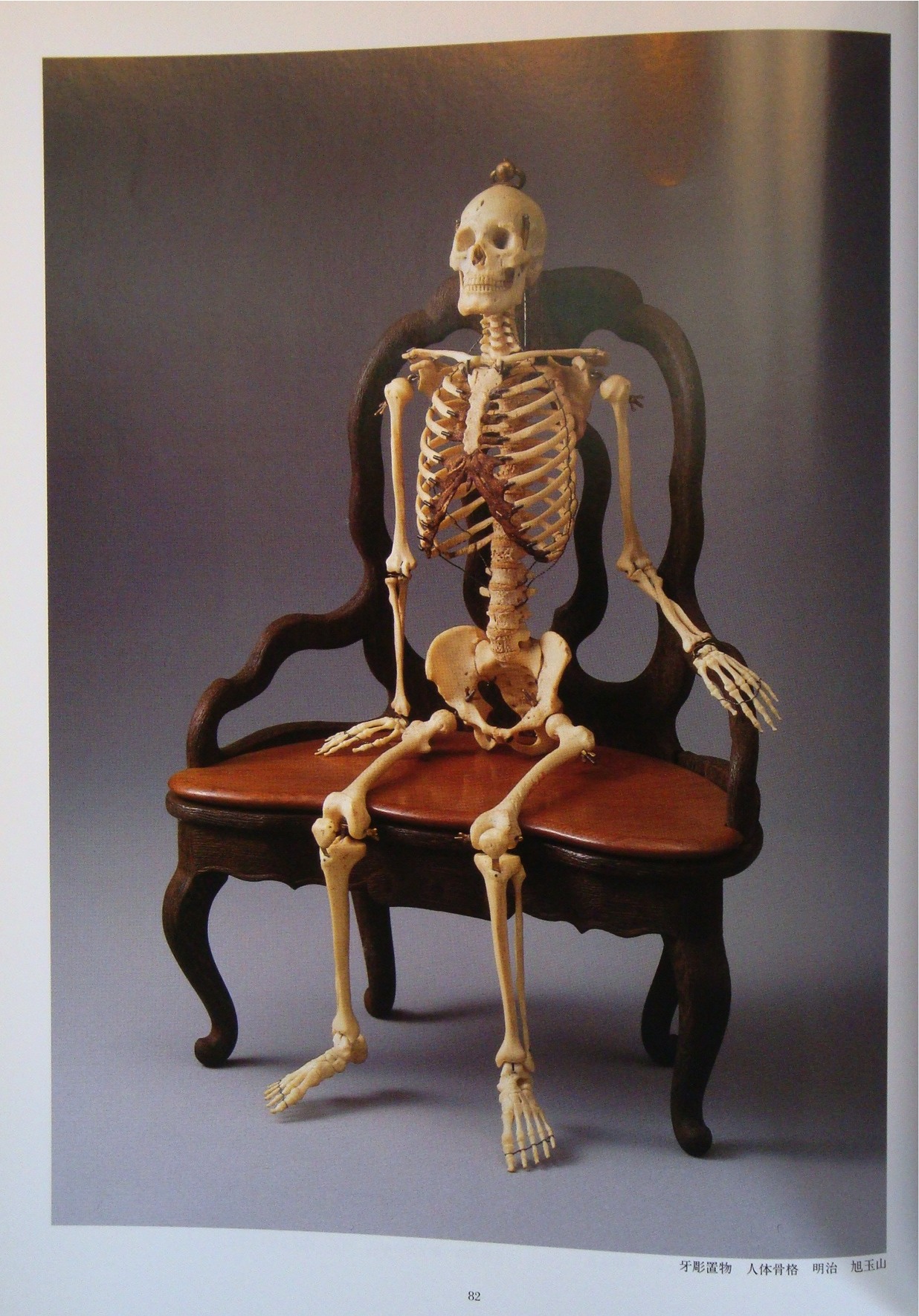

cf. Fukui Yasutami, History of Japanese Ivory Carving: Gebori-Okimono and Shibayama of Meiji Period, 1996, pp. 82-83

Arts of East and West from World Expositions: 1855-1900: Paris, Vienna and Chicago, Nagoya, Japan, 2005, p. 44, no. I-92The art of carving okimono (object for presentation) developed from the art of carving netsuke. The latter developed in many schools and reached its peak towards the end of the Edo period, around 1868. This rapid development foundered in the Meiji period (1868-1912), when western fashion asserted itself in Japan. At that time, many netsuke carvers turned to okimono, which were highly fashionable and much appreciated in the West. A number of artistic academies also opened in Japan, such as the Art Academy Tokyo in 1889 where, among others, the famous ivory carver Ishikawa Komei (1852-1913) taught. The artists studying at these academies became familiar with western artistic trends and were able to create works of art that appealed to European taste while still retaining the typically Japanese elements of precision and simplicity.

Exhibits of Japanese works of art were inundated with awards at the international exhibitions including Vienna (1871), New York (1876), Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1878, 1879, 1900), Amsterdam (1883), Chicago (1893) and London (1910). Works in ivory were exhibited at these fairs and visitors reported that some of the Japanese stands were so full of ivory pieces that they looked as ‘white as snow’. As a result, the Japanese art of ivory carving was widely recognised and highly praised by artists, critics and collectors.

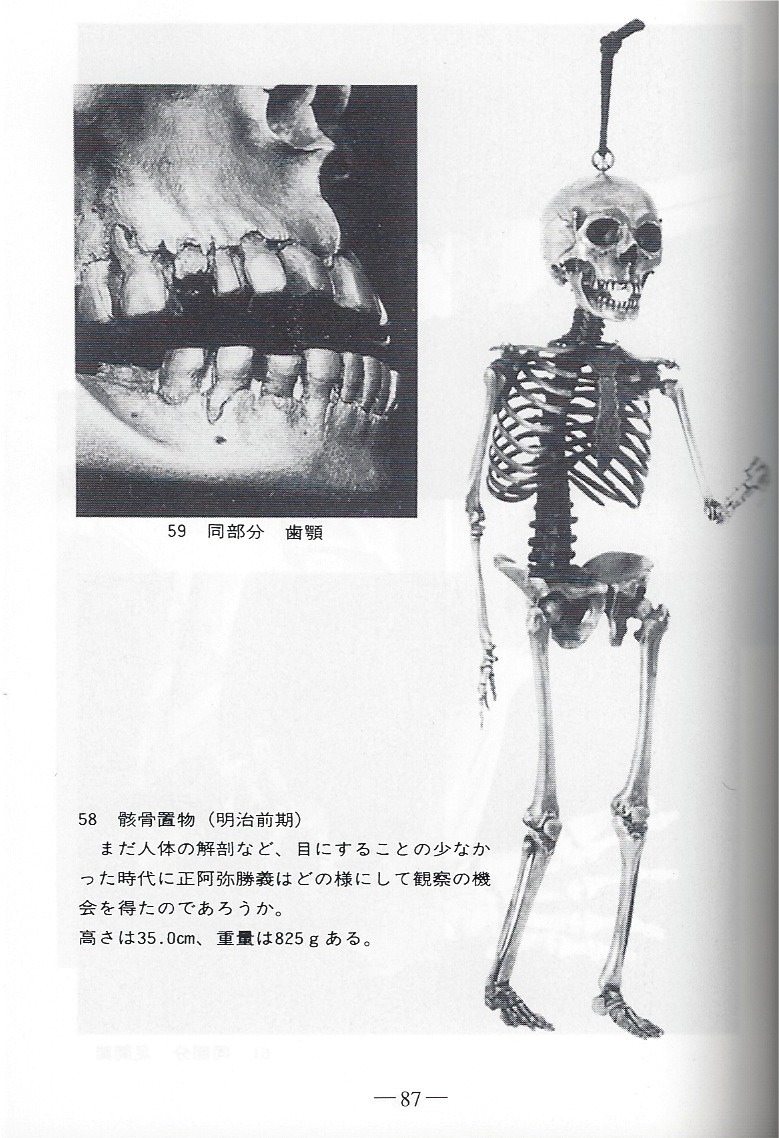

The finest ivory carvers of the Meiji period produced works of breath-taking quality, like this highly realistic model of a skull, signed by the carver Shosai. Production was limited due to the time it took to complete these intricate sculptures; it was said that production of a good okimono could take up to three years. Shosai, active from the beginning of the Meiji Period until the end of the Second World War, was a student of Naomitsu and teacher of Shoraku and Shoju. He was well known for his depiction of skulls. His work may be compared to one of the best-known ivory carvers of the Meiji era, Asahi Gyokusen (1843-1923) who was also admired for his realistic carvings of skulls. An ivory carving of a human skull by Gyokusen is held in the Tokyo National Museum (illustrated in Arts of East and West from World Expositions: 1855-1900: Paris, Vienna and Chicago, Nagoya, Japan, 2005, p. 44, no. I-92). Its intricately detailed carving closely matches this skull by Shosai, suggesting that these artists were working concurrently, and probably trained in similar schools of ivory carving.

The skull is the Japanese Buddhist symbol of Yama, the god of the dead, and it appears frequently in sculpture of the Meiji period. Though reminiscent of death, the skull is believed to be a sign of good luck, a charm to remind one of the transience of life. Japanese folktales, legends and ghost stories from the Edo and Meiji Period reflect a fascination with the supernatural and the after-life, and feature skeletons and skulls. These Japanese memento mori found resonance in Europe, and became highly sought-after in the West.

An ivory okimono in the form of a skull by Gyokusen, of similar quality, is held in the collections of the British Museum. Other smaller netsuke ivory carvings of skulls are held in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Art.